Why Adolescence poses difficult questions for British TV

ScreenPower: where TV and Film meet politics and power

Hello and welcome to ScreenPower: a newsletter about the UK’s film and TV industries - and how they’re impacted by politics and power.

First, welcome to new subscribers! I hope you find this free newsletter interesting and useful. You’re now part of a growing community of ScreenPower readers from a huge range of organisations:

In today’s edition:

👊 1. The big questions that Netflix drama Adolescence poses for Britain’s broadcasters…

👊 2. Three trends you should be keeping an eye on in the US, that could have ramifications here…

👊 3. And what's your experience engaging with DCMS Ministers?

Here goes… 📽️💪💥

1: 📺 What the success of Netflix’s Adolescence says about the state of British TV

This weekend I finally gave in to peer pressure and the unrelenting Netflix PR machine and started watching Adolescence.

It certainly lives up to the hype (even just for the incredible one-take episodes) - and I can see why it’s raised questions around challenging topics like toxic masculinity, social media, and how we raise our children.

But the big question for me is what this drama says about the state of scripted TV in the UK, particularly for Britain’s public service broadcasters (PSBs).

Distintive

The UK’s PSBs are proud of their reputation for making ‘distinctively British content’ - the types of shows that spark national conversations.

It helps to define them. Channel 4 says ‘distinctive British content’ is what makes it ‘stand out in the media landscape’. It’s even required by law to make content that ‘exhibits a distinctive character’.

And Channel 5’s boss Sarah Rose told the VLV conference last year about the broadcaster’s duty to tell original stories that “reflect Britain back at itself”.

For PSBs, ‘distinctive British content’ is sort of their thing - and it’s a space they’ve successfully carved out over decades.

ITV’s Mr Bates vs The Post Office is the recent stand-out example of a show that prompted an important national debate - but shows like It’s a Sin, Sherwood and Help have also captured moments and moods.

‘World TV’

Those examples have been used to draw a line between national broadcasters and global streamers - with a characterisation that the latter is only interested in commissioning shows with broad international appeal, and thus not distinctive to any single country.

‘World TV’ was a term coined a few years ago to describe this genre, and Netflix’s Sex Education has occasionally (somewhat unfairly) been held up as an example: a show shot in Britain with British actors, but with an occasionally more generic international feel to it.

It’s previously been a concern for politicians. Sir John Whittingdale spoke about this at the RTS Convention in 2021 when he was a DCMS Minister - about the need to protect distinctive British content both for its importance to British audiences, and to project British values abroad.

And last year, ITV told MPs that “international customers increasingly want content that travels well globally and are, therefore, less interested in British and in particular niche British content”.

That may be so, but Adolescence is doing a pretty good job at debunking the argument that only PSBs can make nationally relevant content. There’s a huge buzz about the show and the challenges it raises. Prime Minister Keir Starmer has talked publicly about it, and there are calls for it to be shown in schools. It’s hard to think of a clearer example of sparking a national conversation through television.

Also, if I were Netflix, facing growing calls for a streaming levy to fund British public service content, this is **precisely** the kind of show I’d be funding - and promoting heavily. To top it off, it was shot in West Yorkshire - neatly addressing political concerns about the creative industries being too focused in the South East.

Globally relevant

But as well as sparking debates at home, Adolescence has seen phenomenal success abroad.

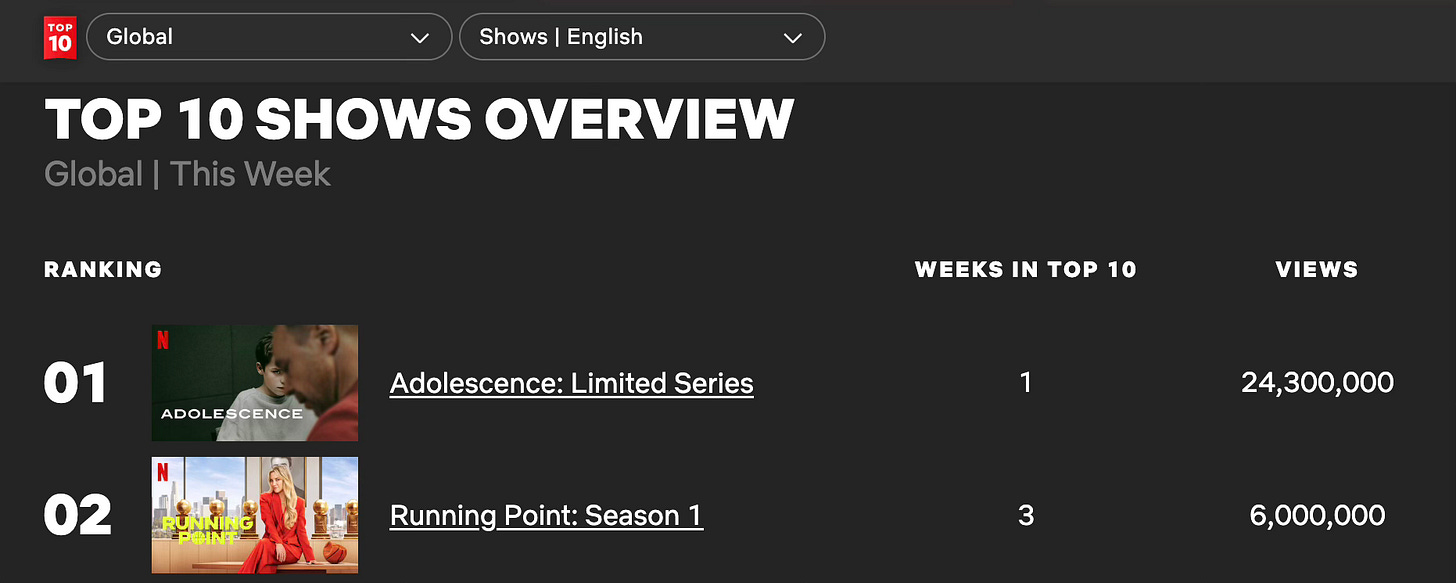

At the time of writing, it’s the number one show on Netflix globally - with more than 4x the number of views (24 million) as the next most popular show.

Unlike Mr Bates, Adolescence is not a solely British story. It addresses societal themes that will have resonance in dozens of countries.

Look at the alphabetised list of countries on Netflix, and it will take you until Hong Kong to find a place where Adolescence isn’t in the top 3 (in Hong Kong it’s #5).

Maybe Netflix’s commissioners could see that international potential in Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham’s drama from the start. But global popularity doesn’t necessarily mean it’s easy to get made. In fact it’s getting harder.

Challenges

Jane Featherstone produced Black Doves for Netflix. In January she explained the squeeze in British-made drama to MPs:

“The deals that we can now establish with the streamers are largely based on one fee that you get. In success, there is not much of an uplift, which makes it difficult for us is to build long-term sustainable businesses. We have effectively gone from being a manufacturing industry to a service industry in respect to the streamers.”

The Sunday Times’ William Turvill wrote a piece earlier this month - ‘British stories are dying out’ - which is well worth a read. Channel 4’s boss Alex Mahon told him “Netflix and Disney are able to spend big budgets per show because they can recoup it globally…so the revenue they can earn per hour means they can pay a higher cost per hour.”

This has caused inflation in production costs - adding a major pressure to PSBs’ ability to fund the content they want to make. Jane Featherstone’s take is that “we are at a place now where budgets have become so high that it has priced the public service broadcasters pretty much out of the market.” Couple that with the broader financial and existential challenges facing broadcasters, and you create a situation where some important programmes simply won’t get made.

ITV have previously warned MPs on the Culture, Media and Sport Committee that “rising costs and stagnating commissioning budgets mean the margins for very distinctively British content are narrowing.”

Big implications

Some shows are made thanks to a mixture of funding from both broadcasters and streamers - but even that route may soon no longer be viable. William Turvill reports “a suspicion that streamers are increasingly wary of co-funding productions and that they would prefer to control all of a show’s intellectual property”.

So are we getting to a place where only the streamers can afford to make big dramas that capture a national moment? And if so, is that so bad?

Aside from what that would mean for the PSBs themselves, it potentially has implications for the types of dramas we could see on our screens. “Netflix and Amazon need to serve their British audience too”, says Jane Featherstone, “but the costs of that production means it has to be successful around the world”.

What’s next?

There are - inevitably - a number of ideas currently doing the rounds in TV land for different versions of Government support for British drama. It’s likely we’ll hear more about this when the Culture, Media and Sport committee publishes its inquiry into British Film and High End TV (expected soon).

It’s a big ask at a time when public spending is so tight - and there will be some who are uncomfortable ideologically with the idea of the state getting involved here.

But the problem for Government is that they’re already involved. In fact they’re up to their elbows in it. British TV is a highly intervened-in space (Adolescence had Government tax credit support) and the inflation in production budgets for high end drama has been driven, at least in part, by tax incentives that attract big-spending US studios to make shows here. There’s certainly an argument that the tax incentive regime has been a victim of its own success.

But besides the financial ask, giving Government a say in what sort of content is and isn’t distinctively British is not somewhere we should want to go.

It would be much better to strengthen the hand of the PSBs - who are already incentivised and required to tell these stories - to commission the sort of shows we’re talking about here.

As ever, I would love your thoughts. In the meantime, enjoy this incredible drama.

P.S. Behind the scenes

If you’re scratching your head as to how they made those amazing one-take episodes, you might enjoy this great behind the scenes video from Netflix. (I still don’t get how they got the camera through that classroom window though!)

P.P.S. Adolescence was made by five independent production companies: Matriarch Productions (Stephen Graham’s company), Plan B Productions (Brad Pitt’s company), One Shoe Films, It’s All Made Up and Warp Films.

2: 🇺🇸 Keeping an eye on developments across the pond 👀

I’ve written before about how exposed parts of the UK’s screen sector are to decisions made in California. Well that applies to the White House too - and it’s worth just keeping an eye on a few developments over there that could impact our industry here.

📈 Ad market ⬇️ : Sara Fischer of Axios reports that “President Trump's economic policies could slow advertising growth in the U.S. through at least 2027”, according to a new projection. That sentiment could seep into the UK market - especially through big multinationals with global marketing budgets. Not great if you’re a PSB still largely reliant on ad spend - nor for streamers whose most profitable subscription tiers (per user) are those with ads.

📊 Inflation ⬆️: The FT reports that leading economists have increased their estimates of inflation in the US, amid uncertainty around Trump’s economic policies. What would that mean for screen? Well it’s already more expensive to make a TV show in the US than the UK. But further pressures over there could mean more productions coming over here to shoot - which may be a double-edge sword. Richard Tulk-Hart of Buccaneer Media (Marcella and Irvine Welsh’s Crime) told Broadcast last week: “Those US shows coming in are going to be more expensive, there’s no doubt. We can make them for less here, but they’re still going to be £4m per episode instead of £2m, and that’s basically going to put us through what we’ve just experienced, which is inflation in the production space. And that is going to only do a disservice to UK shows.” V much links to the story above about British drama.

💰US tax incentives ⬆️: There’s also the risk that the opposite could happen at some point too - that fewer US productions could come over here to shoot, with serious implications for British jobs. The Directors Guild of America said last week that “with production in decline worldwide as studios and streamers pull back on spending on new projects” their efforts will now be focused on “ensuring that the production that remains in America is not further lost to countries offering more favourable tax programs” - like, ahem, the UK. The DGA are supporting efforts to double the tax incentive available in California - and there are calls for a federal tax film tax incentive too. Could this tempt big budget shoots to stay stateside? There’s certainly lots of talk about this in the US at the moment - including from Trump’s ‘Hollywood Ambassador’ Mel Gibson who told Fox News “there’s something wrong” with the current set up (2’40 in the clip below).

3. I need YOU 🫵🙏

I’ve been hearing quite a lot lately about the difficulties people are having when they try to engage with Ministers at the Department for Culture, Media and Sport. This is purely anecdotal - but it’s not restricted to the screen sector. I’m hearing this from people across the creative industries.

Tough gig: Obviously, DCMS is an incredibly busy department, with hundreds of different organisations wanting to get a hearing. But most of the anecdotes are based on comparisons with previous administrations.

🧐 Deep dive: I’m going to look into this properly for a future edition, so I would love to hear your thoughts and experiences - whatever sector you work in. Get in touch by replying in confidence to this email, or messaging me on LinkedIn, and tell me:

Have you had a good or bad experience trying to engage with DCMS since the new administration came in?

What’s the quality of the engagement?

How does that compare to previous years?

Do you feel like DCMS Ministers understand the key issues facing your sector?

Identity Protected🚫: I realise this is a sensitive business, so you have my word that I will offer full witness protection guarantee your anonymity. 🙏

Also it seems like a good time to test this Substack feature:

🎞️ Recommend ScreenPower

Thank you for reading ScreenPower! As ever, do get in touch with any comments or questions on the topics covered in this issue, either by replying to this email or by connecting on LinkedIn.

And if you know someone who might enjoy this - why not forward it to them? It’s free!